At ShardSecure, we often write about cross-border data protection from a compliance standpoint. Whether we’re talking about the EU’s GDPR, Asia’s APEC Privacy Framework, or even Canada’s PIPEDA, it’s crucial to comply with government regulations for personal data.

But there’s another element of cross-border data protection that also can’t be ignored: cybercrime.

Globally, cyberattacks are expected to cost the world almost $600 billion, or nearly 1% of global GDP, per year. One report estimated that approximately $5.2 trillion will be at risk from cyberattacks from 2019 to 2023 alone. Another suggested that annual damages from cybercrime will reach $10.5 trillion by 2025.

Today, we’ll take a look at cross-border cybercrime. What’s fueling the attacks? What obstacles do prosecutors face in bringing international criminals to justice? Most importantly, what can we do to stop attackers?

Let’s dive in.

The criminal landscape

While cybercriminals can operate from almost anywhere in the world, some locations are hotspots. According to the Global Tech Council, China, Russia, Brazil, Poland, Iran, and Nigeria are among the top countries of origin for attacks — typically with targets outside their own borders.

A country may become a hotspot for online criminal activity or cyberterrorism if:

- It’s experiencing rapid technological growth.

- It has high unemployment rates.

- Its authorities don’t crack down on cyberattacks.

- Its leaders tacitly condone attacks.

The impact of groups like pro-Russian hackers, Chinese government hackers, and state-sponsored cyber warfare units cannot be denied. That said, organized crime groups tend to pose a bigger threat to data security than cybercrimes carried out by nation-states. In 2020, organized crime was behind 55% of all data breaches, and it’s only grown more sophisticated and coordinated since then. Now, cybercrime gangs often have connections with each other and may even openly collaborate on tactics and techniques.

In fact, the ease with which organized crime happens in cyberspace has led the UN to describe it as a “borderless” rather than cross-border problem. Today, almost anyone can be attacked by organized criminals operating almost anywhere in the world.

Is the cybercrime problem growing?

In a word, yes. The Center for Strategic and International Studies and McAfee put it plainly in a joint security report: “Cybercrime is a growth industry. The returns are great, and the risks are low.”

One reason for the rise in crime is the interdependence and interconnectivity of global digital systems. Coordinated groups of attackers can use this interconnectivity to cause great damage to public and private ecosystems.

Another major contributor is the relatively slow response of law enforcement. While criminal laws now exist to punish cybercrime, most regulators are still playing catch-up. As the United Nations describes, although 156 countries have now enacted some kind of cybercrime legislation, “The evolving cybercrime landscape and resulting skills gaps are a significant challenge for law enforcement agencies and prosecutors, especially for cross-border enforcement.”

And cross-border enforcement is increasingly the norm. With so many attacks originating outside a country’s borders, it can be nearly impossible to prosecute criminals without the cooperation of other nations. Even gathering evidence from telecommunications and cloud service providers overseas can be challenging, laborious, and time-consuming.

So, what can be done about cross-border cybercrime?

Some attempts have already been made to fight global cybercrime. In May 2022, nearly two dozen countries signed the Council of Europe’s Second Additional Protocol to the Budapest Convention. The protocol is intended to fight cybercrime by enhancing international cooperation on criminal investigations and facilitating electronic evidence gathering.

Many critics, however, point out that the protocol is heavily skewed towards increasing police powers to the detriment of data privacy rights. Other commentators have pointed out the risks of this protocol for journalists, human rights activists, and vulnerable populations in countries whose governments treat free speech and dissent as crimes.

Although activists continue to advocate for fair, just legislation, the threat remains. As a result, it’s largely up to organizations to protect themselves against international cyberthreats.

ShardSecure: strengthening your cross-border data protection

One way to mitigate the impact of international cyberattacks is with microsharding. By shredding data into tiny pieces (microshards) and then distributing those microshards across multiple customer-owned storage locations, ShardSecure ensures that datasets are unintelligible to attackers — wherever they may reside. This approach protects companies from the impact of data exfiltration in increasingly common double-extortion ransomware attacks.

Microsharding can also reconstruct data when it’s lost, deleted, compromised, or encrypted by ransomware. Instead of losing valuable information and suffering from downtime during cross-border cyberattacks, companies can instead use our self-healing data to restore microsharded data transparently and in real-time. Your business might be staving off an attack from the other side of the world, but your users will be able to continue working uninterrupted.

Check out our many resources on microsharding to learn more about cross-border data protection with ShardSecure today.

Fachartikel

Studien

Drei Viertel aller DACH-Unternehmen haben jetzt CISOs – nur wird diese Rolle oft noch missverstanden

AI-Security-Report 2024 verdeutlicht: Deutsche Unternehmen sind mit Cybersecurity-Markt überfordert

Cloud-Transformation & GRC: Die Wolkendecke wird zur Superzelle

Threat Report: Anstieg der Ransomware-Vorfälle durch ERP-Kompromittierung um 400 %

Studie zu PKI und Post-Quanten-Kryptographie verdeutlicht wachsenden Bedarf an digitalem Vertrauen bei DACH-Organisationen

Whitepaper

Unter4Ohren

Datenklassifizierung: Sicherheit, Konformität und Kontrolle

Die Rolle der KI in der IT-Sicherheit

CrowdStrike Global Threat Report 2024 – Einblicke in die aktuelle Bedrohungslandschaft

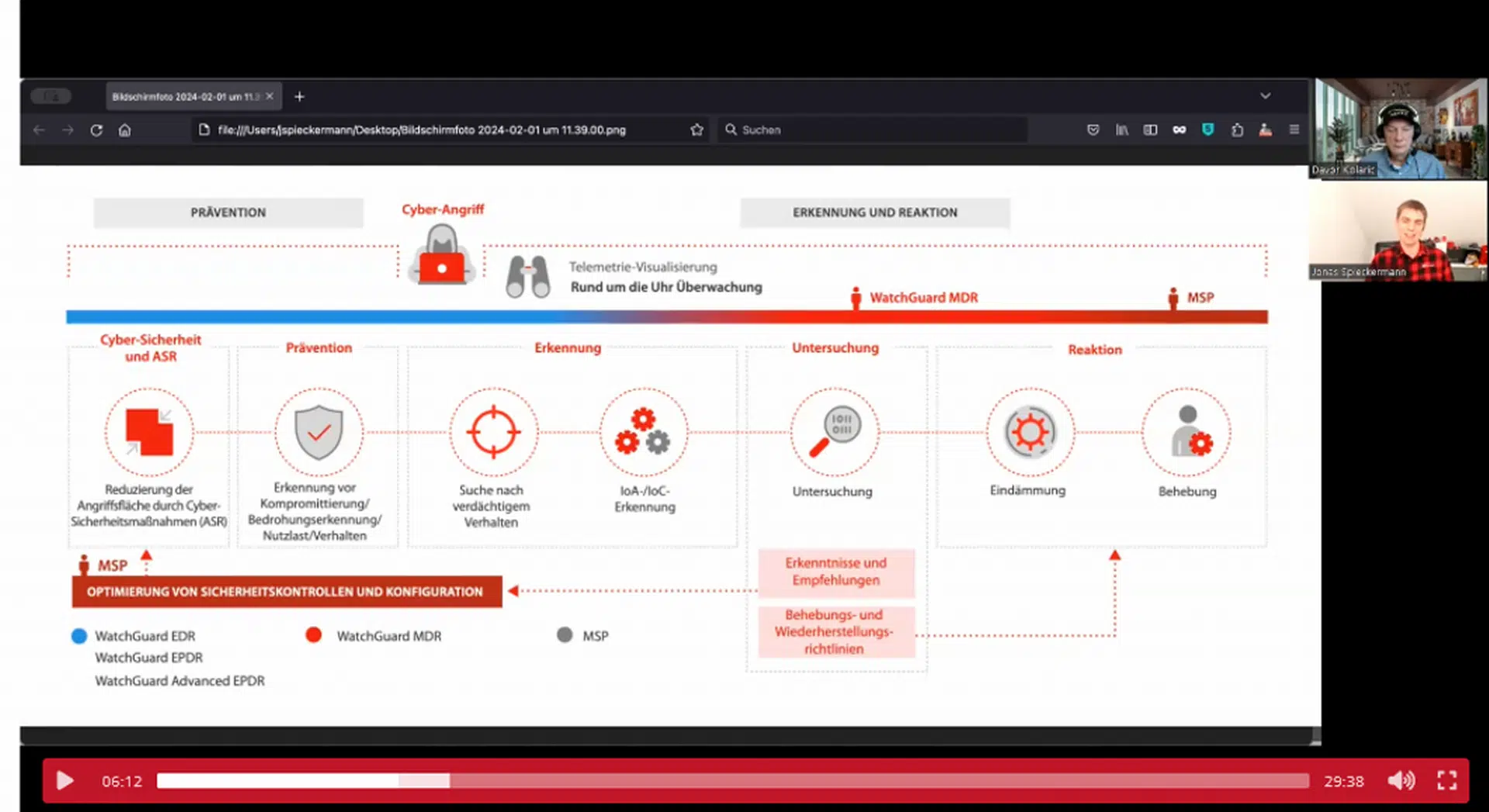

WatchGuard Managed Detection & Response – Erkennung und Reaktion rund um die Uhr ohne Mehraufwand